This analysis is part of The Leonard D. Schaeffer Initiative for Innovation in Health Policy, which is a partnership between the Center for Health Policy at Brookings and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

With Republicans now in control of the Presidency, Senate, and House of Representatives, they have the opportunity to fulfill their repeated promise to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA). They banded together to pass repeal alone early this year (albeit knowing it would get vetoed by the president), but no detailed consensus replacement plan has emerged.

There has been no shortage of ACA replacement plans put forward by think tanks and members of Congress, including Speaker Paul Ryan’s Better Way, HHS Secretary nominee Tom Price’s Empowering Patients First Act, and the Patient Choice, Affordability, Responsibility, and Empowerment Act (P-CARE) led by Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch, House Energy & Commerce Chairman Fred Upton, and Senator Richard Burr, but many are still in outline form or lack critical details and none has been voted on or scored by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Despite the lack of consensus on what a replacement plan looks like, Republicans are signaling that they plan to use the budget reconciliation process (which only requires a simple majority in the Senate rather than the 60 votes needed to bypass a filibuster) to pass a law immediately that repeals the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, premium tax credits, cost-sharing assistance, and the taxes that helped pay for it (leaving in place the law’s insurance market and Medicare reforms) as of a date certain in the future (likely January 1, 2020). The delayed effective date is supposed to give lawmakers time to craft a replacement without disrupting coverage in the interim.

President-elect Trump and Congressional Republican leaders have staunchly expressed their intent to replace the ACA but keep in place some key popular features of the law such as the ban on discriminating based on pre-existing conditions. If replacing the ACA is truly the goal, though, repealing it first without a replacement in hand is almost certainly a disastrous way to start.

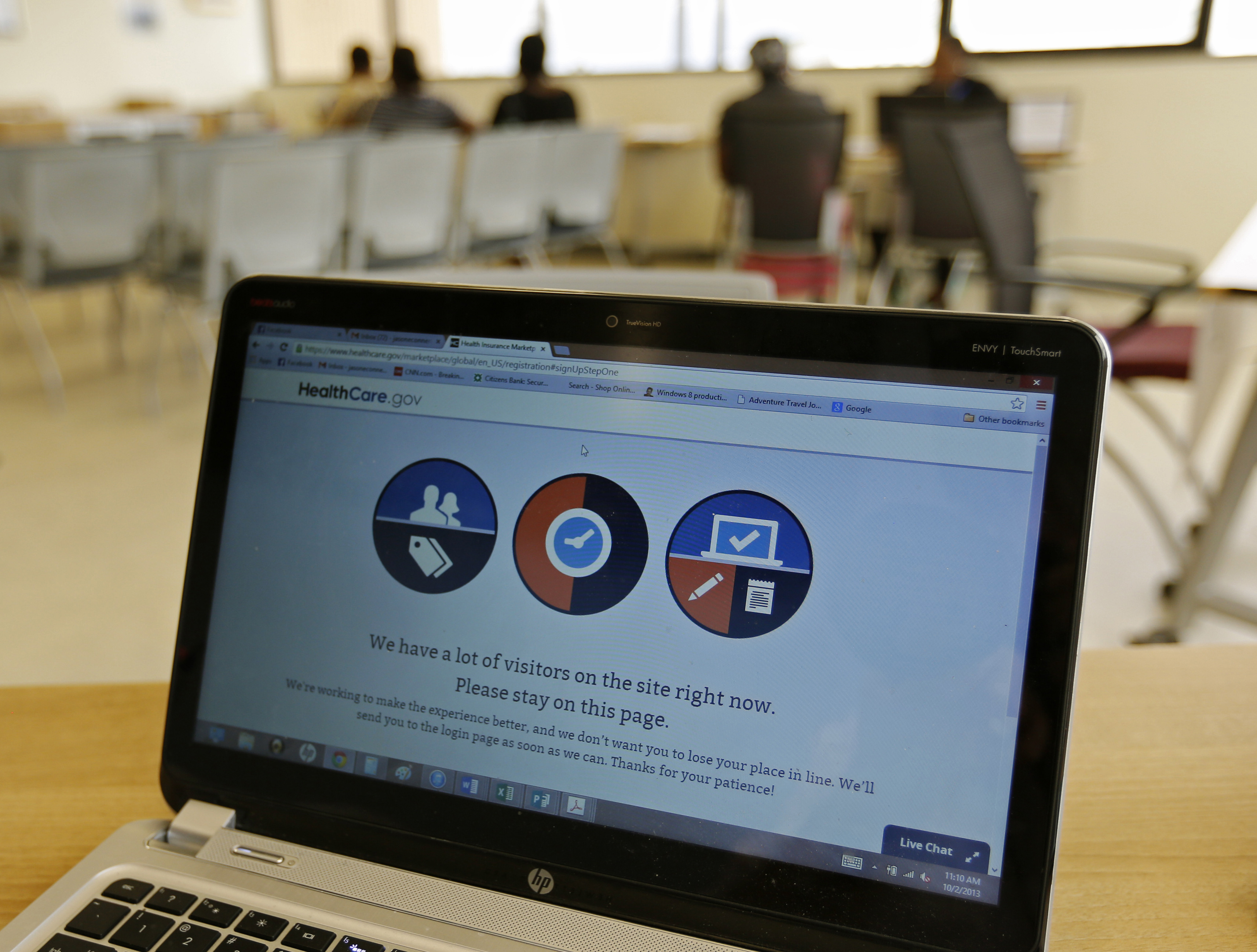

First, a reconciliation bill (like the one passed in 2016) would likely destabilize the individual market and very possibly cause it to collapse in some regions of the country during the interim period before any replacement is designed. That’s because some insurers that have stayed in the individual insurance market in hopes of adding customers as they gained experience with the ACA marketplaces would likely pull out of the individual market under the “repeal and delay” scenario, in the face of the law’s uncertain future and thus unpredictable enrollment and costs.

Second, insurers that do remain would be inclined to raise their premiums to account for that uncertainty and because the reconciliation repeal bill would immediately eliminate the individual and employer mandates that help increase enrollment of healthier people. CBO estimates that eliminating the individual mandate would alone increase premiums by 20%. This combination, in turn, would cause a substantial number of those currently with insurance, especially younger healthier ones, to drop their insurance, leaving an even sicker risk pool in place and increasing premiums even further.

Researchers at the Urban Institute estimate that the market destabilization caused by “repeal before replace” would increase the number of uninsured by 4.3 million people near immediately.

To avoid this result, Republicans would need to devote additional money to stabilizing the ACA’s marketplaces, through such measures as bringing back limits on insurer losses and profits (known as “risk corridors”) and subsidized reinsurance (which helps cover the costs of the most expensive enrollees). However, Republicans spent the last few years decrying these measures as “insurer bailouts,” and suing to stop the law’s cost-sharing subsidies.

Even if lawmakers can agree on spending money to stabilize the market during the “delay” period, there’s no guarantee that a replacement plan will garner sufficient support to pass Congress. A reason for this is that any replacement reforms will require some level of bipartisan backing to get past a filibuster in the Senate, which requires 60 votes (Republicans will only control 52 seats, at least until 2019), and probably to hold a sufficient number of Republicans in the House of Representatives (where some may balk at the cost of any suitable replacement).

Starting with repeal also makes replacement more difficult by eliminating $680 billion (over ten years) worth of taxes on high-income households and the health care industry that helped pay for the ACA’s coverage expansion. Even incorporating the dynamic effects of ACA repeal (CBO estimates that ACA repeal would slightly increase economic growth, and in turn revenues), the reconciliation bill passed in 2016 would have saved $516 billion on net over ten years, leaving only roughly half the amount spent by the ACA to pay for replacement coverage provisions. Moreover, given that the costs of repealing the ACA’s taxes, and the so-called Cadillac tax in particular, grow faster than the savings from eliminating the coverage provisions, the reconciliation version of repeal would actually increase deficits in the long run.

Lawmakers could generate some additional revenue by capping the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance, as many of the Republican replacement plans propose, but unless the cap were set significantly lower than that of the ACA’s Cadillac tax, such a policy would not raise much more than $100 billion over ten years. It could raise more if the cap were set lower or gradually lowered over time, but given how difficult the Cadillac tax has proven to sustain, doing so would not be easy.

If no replacement plan materializes, the hollowed out individual market – for people without access to employer-provided or public coverage – could be left in shambles. Because reconciliation is a process intended only to modify provisions that directly impact the budget, repeal through reconciliation will eliminate the Medicaid expansion and subsidies to buy private insurance, for instance, but likely leave the ACA’s insurance market regulations in place.

With the ACA regulations that ban insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on pre-existing conditions remaining, but without the law’s significant subsidies or mandates, the individual market is very likely to enter a “death spiral.” Without subsidies or the individual mandate, many healthy people will exit the market and choose to go uninsured, which will cause insurers to raise premiums further to account for the now sicker, on average, enrollment, which in turn will cause more and more healthy people to rescind their coverage, and premiums to rise further.

And this expectation isn’t just theoretical. The insurance market in New York before the ACA illustrates roughly what happens when insurers have to offer coverage without subsidies but cannot charge differential premiums based on health status – extremely high premiums and extremely low enrollment. In this situation, people without access to employer or public coverage would be left without affordable insurance options.

A death spiral in the individual market would harm more than just the 9.4 million beneficiaries of the ACA premium subsidies.

Under the ACA, the number of people who purchase insurance through the individual market has grown from roughly 10.5 million before the law to about 18 million people today, roughly half of them purchasing insurance off the exchanges. Full repeal of the ACA, then, would be expected to shrink health coverage through the individual market roughly back down to 10.5 million.

Health Access & Equity Paying for an ACA replacement becomes near impossible if the law’s tax increases are repealed

Loren Adler, Paul B. Ginsburg

December 19, 2016

Health Care Policy 9 questions Americans are—and should be—asking about the American Health Care Act and its projected impact

Caitlin Brandt, Margaret Darling, Marcela Cabello, Kavita Patel

But delayed repeal with the hope of replacement, which eliminates the ACA’s subsidies and mandates but leaves in the place the ACA’s insurance regulations, risks nearly destroying the individual market altogether if no replacement emerges. In its wake, only 1.5 million people would get health insurance through the individual market, 9 million fewer than before the ACA, according to estimates from the Urban Institute and fitting with the experience in New York before the law. A small number of people would instead get coverage through an employer.

Therefore, partial repeal of the ACA through reconciliation would leave even more people uninsured than before the ACA’s passage.

CBO estimates that ACA repeal, including the regulations, would cause 22 million people to lose insurance coverage, but they make clear that the effects would be worse if the law’s insurance regulations remained in place. The Urban Institute estimates that an additional 7.3 million would lose insurance coverage under partial repeal, for a grand total of nearly 30 million people newly uninsured.

Even if repeal through reconciliation is able to eliminate the ACA’s insurance regulations simultaneously, which some have argued is possible, that still would leave in its wake over 20 million uninsured. Unless Congress left intact the ACA’s restrictions on pre-existing conditions and guaranteed issue insurance regulations, it would also mean going back to the individual market that existed before the ACA where people could and did get rejected for coverage based on a multitude of pre-existing conditions, or had coverage rescinded when they became sick.

Insurance industry estimates from 2008 found that 13% of people who applied for coverage in the individual market were rejected outright, as were 29% of people aged 60-64. And these figures don’t even include the numerous people who didn’t bother applying because they knew they would be rejected, as a result of prior rejections or a broker’s advice, or the 34% of people offered a policy only without coverage for their pre-existing condition or at significantly higher than standard rates

If replacing the ACA with something better is the goal, as President-elect Trump and Congressional Republican leadership have indicated, then repeal should happen simultaneously with replacement. Fortunately, President-elect Trump has indicated a desire not to repeal without a replace plan in-hand, and Senator Lamar Alexander (chairman of the powerful Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee) has also expressed a preference to “replace then repeal.”

In taking a different direction, a replacement plan should also focus on fixing the key problems currently facing the ACA: insufficient incentives for the young and healthy to buy coverage; risk adjustment and adverse selection challenges; a lack of competition in many regions; and the unpopularity of the individual mandate.

Taking this approach, a workable replacement plan that might be acceptable to the new Congress would:

If lawmakers wish to go farther, they could also make more expansive changes in the current structure:

The current situation presents an opportunity to replace the Affordable Care Act with a more sustainable bipartisan law. But repeal must wait until a consensus is built around a replacement plan. Not doing so – starting with repeal and delay – threatens to destabilize the individual market and harm not only those who receive subsidies from the ACA, but also everyone who now purchases insurance in the individual market.

Estimates show that premiums would jump at least 20 percent and cause 4.3 million to lose health insurance as soon as next year, and that’s nothing compared to the damage that would be inflicted if a replacement plan subsequently failed to emerge. The current version of repeal through reconciliation, leaving in place the ACA’s insurance market reforms, would nearly destroy the individual market if its provisions took effect, causing 30 million people in total to lose health insurance, leaving more uninsured than before the ACA.

Fixing the ACA is important, but replacing it with a durable plan to make health coverage broadly affordable will take time and constructive bipartisan collaboration.